THE LIFE AND DEATH OF A DALIT JOURNALIST

The circumstances of Nagaraju Koppula's death point to reasons why our newsrooms continue to be incapable of absorbing people from disadvantaged backgrounds.

In a heavily contractualised media industry, unions have become a bad word and journalists associated with unions have come to be looked on as trouble makers. It's no surprise, then, that lawyers, academics and activists outnumbered journalists at the condolence-cum-stocktaking meeting called on by the Delhi Union of Journalists (DUJ).

The motley group of people had gathered at DUJ's run-down headquarters in the heart of Delhi to condole the death of Nagaraju Koppula — a young, and possibly the lone, Madiga Dalit journalist who worked at The New Indian Express in Hyderabad.

DuJ members and many present at the meeting squarely put the blame on Nagaraju's employers for his worsening health that ultimately led to his death on April 12.

Talk flew thick and fast of the media's apathy towards its own people. Some wondered why so few journalists had come forward in support of Nagaraju and why his case had not been reported on by any of the media houses. "Is there no news value for his story? If not, it should be created," said one of the speakers.

'I want to make it as an English journalist'

Journalist Paranjoy Guha Thakurta, present at the DUJ meeting, had taught Nagaraju in a creative writing course at the-now defunct Tehelka School of Journalism in Delhi. Nagaraju later helped him in one of his documentary movies as a translator. He was, as Thakurta says, "the only student on scholarship in a class full of rich kids." He speaks of Nagaraju's "amazing determination to overcome his underprivileged background" – a fact most of his colleagues and friends confirm.

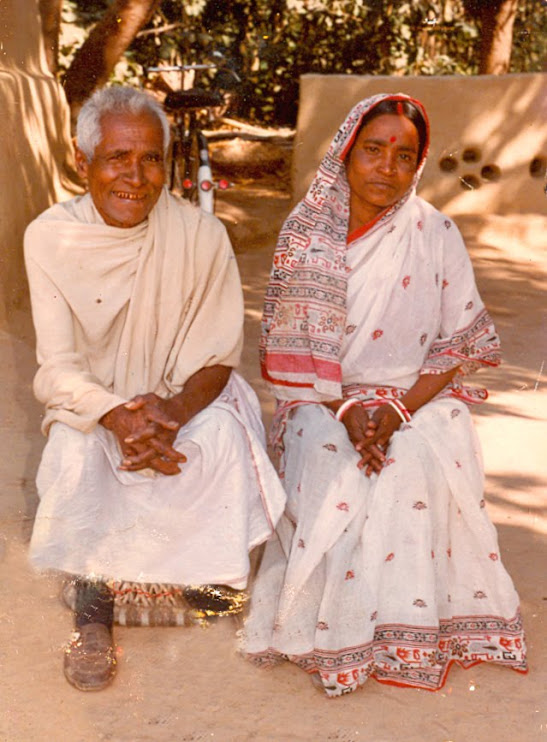

Born in Sarapaka village in Khammam district, Nagaraju lost his father when he was very young. He along with his mother and five siblings lived in a small thatched hut on the banks of the Godavari next to the ITC factory. According to his friends, Nagaraju grew up doing odd jobs like selling ice to fund his education through school. Later, he started painting signboards in his village and collected enough money to go to college and apply for a Masters in History at the University of Hyderabad.

"He is a very famous painter in his village. When I went to his funeral in Sarapaka, people showed me a big beautiful board of Kamal Haasan that he had painted. Usually, once people from his background get used to a steady income, they give up on education, but he was committed to studying," says Chittibabu Padavala, an ex-journalist who is now pursuing post-doctoral studies at the Indian Institute of Technology, Bombay.

Chittibabu had met Nagaraju on the campus of the University of Hyderabad and convinced Nagaraju to join journalism. "I convinced him to join journalism. I consider myself criminal number one," he says.

Chittibabu himself belongs to a Dalit sub caste and says he had always believed there was a need for more Dalits to join journalism. He has worked in organisations like The Hindu and Frontline and expresses his discomfort at talking about his own experiences as a Dalit in Indian newsrooms. "I'd rather be known as a public intellectual who speaks for Dalit rights and not for my experiences as a Dalit," he says.

Nagaraju joined the Indian Institute of Journalism and New Media,Bangalore, after his masters on concessional fees and then went on to pursue a creative writing course in Delhi. Despite his qualifications, he found it tough to get a job in media organisations after he passed out from IIJNM in 2010.

His friends say he was determined to join the English media and didn't want to settle with being a regional language journalist. After three failed attempts at The Hindu, he finally got a job at The New Indian Express in 2011.

"He was an extremely hardworking reporter who could really slog. He covered numerous beats and was very good with research. His English may not have been up to the mark but he more than made up for it," says a batch mate and a colleague of Nagaraju.

"Many of my batch mates joined public relations and non-media companies after they failed to get through mainstream media, but Nagaraju did not quit. His relentless effort finally paid off when he was offered a job by The New Indian Express based on his performance after a three-month unpaid internship. He was really happy when he called me to tell me this," says Gangadhar Patil, another of Nagaraju's batch mate.

'There was discrimination right at the outset'

It is the contention of DUJ and people like Chittibabu that Nagaraju had been discriminated on account of being a Madiga Dalit in a pre-dominantly upper-caste media industry. "From the beginning there seems to be a different pay treatment. He joined at a salary of Rs 15,000, which is less than what the Savarna journalists were getting at that time. His batch mates joining The New Indian Express got close to Rs 20,000," claims a Delhi-based journalist who was close to Nagaraju.

She also claims that his appraisals were low even though he worked very hard and that with his salary, he could not afford a house and stayed with his friends at the University campus. "He had taken a bike on loan and travelled close to 50 kilometres to his office and more for work. He had to send money back home too," she claims, adding that his contract was inclusive of all allowances.

Another journalist based in Hyderabad with a leading English daily states that by 2012, Nagaraju had developed a persistent dry cough and had started to lose weight. "I advised him to visit a doctor. He could not afford medical treatment, even though as an employee he was entitled to a health card," she claims.

After a persistent bout of cough Nagaraju sought medical help under the Andhra Pradesh government's rural health care scheme, Aarogyasri, for those below the poverty line. He went back home for about five months to get treated and visited Hyderabad every month to get medication from the Lung and Chest Hospital in Hyderabad that had diagnosed him with tuberculosis.

His condition only got worse. With the help and insistence of his friends, he sought a second opinion from a private hospital. On April 1, 2013, he was diagnosed with advance-stage lung cancer. So far, he had been getting treated for a disease he didn't have.

DUJ and some of Nagaraju's friends like Chittibabu have claimed that The New Indian Express denied Nagaraju sick leave and that he had to go on a five-month long unpaid leave when he was misdiagnosed with TB. In a press release, DUJ has stated: "When TNIE [The New Indian Express] got to know Nagaraju has terminal cancer, they quietly removed his name from the rolls without following due procedure or even intimating him."

"He visited The New Indian Express' office at least twice in his decaying stage asking if the management could help him in any way," says a close friend who was with Nagaraju through his cancer treatment. Nagaraju's treatment included about six cycles of chemotherapy costing Rs 40,000 each. Most of his expenses were borne by friends and batch mates who came together to raise funds for him though chain mails.

Newslaundry has assessed Nagaraju's offer letter that confirms the assertions about him starting off in The New Indian Express at a salary of 15,000 inclusive of all allowances. However, his contract was not available for scrutiny.

Newslaundry has, however, assessed a 2011 contract of another journalist, also a batch mate of Nagaraju, who joined The New Indian Express in 2010. The contract, written on a bond paper, makes no mention of sick leave or medical insurance. It offers the journalist a remuneration of Rs 22,000 and the journalist has stated that he joined The New Indian Express at a salary of Rs 20,000 in 2010.

Newslaundry has also assessed a series of chain mails beginning April 6, 2013, that have a number of Nagaraju's friends volunteering to support his treatment.

'Don't make this a Dalit issue'

Even as DUJ has stated that he was denied help from The New Indian Express owing to his Dalit origins, some of friends and batch mates claim it wasn't so.

"There is no doubt that the management should have made some discretion on humanitarian grounds. What happened was wrong. But it could have happened to any of us. I don't think he was denied leave or medical help because he was Dalit. All of us had only one month of leave and it is totally on the discretion of the boss whether your leave gets extended. We did have a health card but the process of getting it was complicated and I doubt if it would have been of any use anyway," says a former colleague of Nagaraju who is now working for another English daily in Hyderabad.

He adds that this should not be made into a "Dalit" issue, but agrees that the management should be blamed for not considering his disadvantaged background. MJ Pandey at The Bombay Union of Journalists says one cannot look at this case in terms of whether the management transgressed any law, but look at it as a humanitarian failure.

Entry restricted

Newslaundry sent questions to G Vasu, Resident Editor, The New Indian Express, to seek the management's side of the story. The questions sought specific answers to the management's health insurance and leave policy.

The New Indian Express replied with a notice that its legal team has sent to DUJ.

Whether Nagaraju was discriminated for being Dalit is something perhaps only an independent enquiry can ascertain. It is true that journalism does not pay the best of salaries at the entry level and since most media houses are located in big cities, eking a living as a cub reporter or junior sub-editor can be extremely difficult. Is there an in-built assumption, then, that those who enter the profession have the financial backing to live in cities on low pay? And where does that leave people like Nagaraju who come from underprivileged backgrounds?

Even if the treatment that Nagaraju underwent were not due to his caste, the fact that the profession he so dearly loved has still not built a viable mechanism to absorb students such as him is worth pondering.

If the media, which derives its raison d'être from exposing shortcomings in other fields, is unable to correct its own wrongs, it would be a great travesty.

http://www.newslaundry.com/2015/04/27/the-life-and-death-of-a-dalit-journalist/

No comments:

Post a Comment