| SikhSpectrum.com Monthly Issue No.3, August 2002 | ||

| War Between The Castes by Tim McGirk Copyright © TIME, Asia A new massacre dramatizes the oppression of India's untouchables - but they are now determined to fight back. An invisible line runs through every village in India. It sharply divides the upper-castes from the untouchables, those beneath Hinduism's rigid social hierarchy. That line was crossed in the village of Laxmanpur Bath last Monday when more than 200 upper-caste men, armed with pistols and rifles, stalked through the evening mist with revenge on their minds. The day before, the untouchables, hungry and desperately poor, had tried to harvest a piece of disputed land, and the upper-castes decided it was time to give the millions of untouchables in this north Indian state of Bihar a lesson that neither they nor their kin would ever forget. The gunmen came up from the Sone River, loading their rifles as they walked. Soon they had a cluster of mud huts surrounded. A few of the untouchable men saw the assault force coming and splashed off through nearby rice paddies. The men figured they were the ones the attackers wanted, that the women and children sleeping inside the huts wouldn't be harmed. But this vengeful army spared no one. In all, 61 people were massacred, and most were women and children. For more than two and a half hours, the upper-caste killers went from hut to hut, methodically butchering the untouchables--looking on them as inferior beings, barely human. The position of one woman's body suggested she'd been touching the feet of her murderer, begging for her children's lives. In another hut, the gunmen shot a nursing mother and her baby. They also killed a young woman by thrusting a hunting rifle between her legs and firing off several rounds. After the slaughter, the shooting party went back to the river and vanished in a flotilla of small fishing boats. Only then did the untouchable men dare to emerge from their hiding places. While they ran, their familes had been annihilated. Shivering with anger and grief, an untouchable survivor said grimly: "If we want to live, we have to fight." In fact, their fight has already begun. After centuries of oppression, India's more than 150 million untouchables are determined not to tolerate the deadly abuse any longer. Preferring to call themselves Dalits, (Hindi for "the oppressed"), they are instigating a social revolution that is long overdue, one whose aim is to topple the 2,500-year-old Hindu caste system. Increasingly, Dalits are challenging Hinduism's tenet that a person is condemned to his caste--determining whether he becomes a doctor or a scavenger, whom he marries and his social standing in a complex, ordered hierarchy--all by his actions in a past life. In this rebellion, the Dalits' main weapons are education and the vote. But in some rural areas, where resistance to their demands for equality is entrenched, they have resorted to violence and sometimes gained the upper hand. In Bihar, authorities say it may only be a matter of days before Dalits retaliate for the Laxmanpur Bath massacre. They are armed and organized, and even the arrest of 23 upper-caste extremists has failed to pacify the Dalits. Similar caste warfare and chaos has engulfed the neighboring state of Uttar Pradesh and flared sporadically in much of the rest of India. Says Ram Prit, a 75-year-old Dalit laborer in Bihar: "If you keep pouring water into a rat hole, the rats will come out fighting."

Not surprisingly, many members of the upper castes are resisting any challenge to the old order. In Bihar, high-caste landowners have raised a private army. Called the Ranvir Sena, it has marshalled more than 1,000 armed men, some of whom were probably behind the latest killings. Even Rabindra Chowdhary, a Ranvir Sena leader, concedes that the landlords had cruelly exploited the Dalits. "We were abusive and did not treat these people well," he says. "We do not believe in killing. But if we do not kill, they will think that we are weak." Tension runs high across India, and even the most nonsensical incident can trigger a bloody outburst. In the southern state of Tamil Nadu, a game of tag between higher-caste Thevar and Dalit schoolboys led to the beheading of a Dalit and the revenge killing of 13 people, both Thevars and Dalits, many of them dragged off a bus and hacked to death. In Bihar's Belaur village, a tiff over a pack of cigarettes led to a mini-war between Dalits and the upper-caste Bhumihars that ultimately left 16 dead and dozens wounded. Four years later that feud still festers: more than 350 Dalit families have deserted the village, and the Bhumihars--who patrol at night with guns and spears, ready for attack--cannot hire laborers for their fields. Some Dalits are refusing to carry out their repugnant jobs. "My generation is fighting," says Sri Prakash, a Dalit whose house was set ablaze in a caste feud. "We've told the Thevars we're not going to cremate their dead any more. Let them do it themselves." Dalits make up one-sixth of India's population, yet only a few have managed to occupy top places in society as politicians, lawyers and scientists. A poor Dalit from the state of Kerala, Kocheril Raman Narayanan, encountered discrimination in school and work. And yet this year he rose to become India's President, the first untouchable to hold that largely symbolic post. In the past Dalits had to support their landlords' candidates for public office or be beaten away from the polling booths when they tried to vote; now they are asserting themselves with the ballot, and their newfound power has jolted all of the national political parties. Ram Vilas Pawan, a Dalit member of the Janata Dal Party, is serving as Railway Minister in the current coalition government in New Delhi. Twice now, a Dalit woman, Mayawati, has been elected Chief Minister of Uttar Pradesh, though her last six months in office were squandered in a vendetta against high-caste rivals. Says Mayawati: Earlier I had thought it would take longer, but change is now so rapid that in a few years we will have a Dalit Prime Minister in New Delhi. Religious doctrine has allowed India's version of apartheid to survive Muslim invasions, British colonialism and even 50 years of democracy. Defenders of the caste system usually cite a verse from the Upanishads, Hinduism's ancient sacred texts: "Those whose conduct on earth has given pleasure can hope to enter a pleasant womb, that is, the womb of a Brahman or a woman of the princely class. But those whose conduct on earth has been foul can expect to enter a foul and stinking womb, that is the womb of a bitch, or a pig, or an outcaste." A hymn from the sacred Rig Veda describes how this human stratification came about: a cosmic giant, Purusha, sacrificed parts of his body to create mankind. "His mouth became the Brahman, his arms were made into the Warrior (Kshatriya), his thighs the People (Vaishiya) and from his feet the Servants (Shudra) were born. "Through the centuries, these four main divisions (called varnas), were slivered into more than 3,000 sub-castes, based on the purity of their professions. A goldsmith is higher up the ladder than a blacksmith, and a priestly Brahman, whose rituals bring him in touch with the gods, is highest of all. The untouchables, however, are off the ladder completely. By origin, many were India's dark-skinned first inhabitants, conquered by Aryans and assigned such awful tasks as burning bodies, skinning carcasses and removing "night soil"--human excrement--from latrines. For thousands of years, outcastes were burdened with these denigrating chores.

In many villages, untouchables still live in poverty and subjugation. They are forbidden from entering temples or drinking from the same wells as members of upper castes. It was long customary for higher-caste landlords to deflower a Dalit bride on her wedding night, before her helpless groom. (To cleanse himself after such a dalliance, according to the more than 2,500-year-old Laws of Manu, an upper-caste man must give alms and make "daily mutterings" of prayers.) These Hindu rules are far from even-handed: even today in some parts of India, if an untouchable is caught sleeping with a high-caste woman, both he and the woman are executed. A Dalit also can be considered too uppity, and risks a beating, if he wears a wristwatch or trousers instead of a traditional dhoti or loincloth. In some villages the Dalits are forced to live on the leeward side to prevent the wind that touches their bodies from defiling the upper castes. Faced with such persecution, Dalits are finally running out of patience. What's surprising is that it took so long. Their emancipation began only in this century, behind the efforts of India's two great social reformers, Mahatma Gandhi and Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar, an angry, brilliant Dalit lawyer and politician. Through a scholarship from the Maharajah of Baroda, Ambedkar, an impoverished village boy, studied abroad and eventually earned several degrees. He worked as a financial adviser to the Maharajah but quit in disgust because the prince's upper-caste servants would fling documents onto his desk, rather than hand them to him, for fear of contamination. Yet his genius was unstoppable, as was his grit. "Nothing can emancipate the outcaste except the destruction of the caste system," Ambedkar once declared. "Nothing can help to save the Hindus and ensure their survival in the coming struggle except the purging of the Hindu faith of this odious and vicious dogma." As an author of the Indian constitution, Ambedkar, who died in 1956, secured guarantees for the advancement of outcastes. For decades, these promises were often blocked by upper-caste bureaucrats, but a new generation of Dalits inside the civil service is helping to bring change. In Uttar Pradesh, for example, 150 positions in the elite 540-member Indian Administrative Service are held by Dalits. New Delhi reserves 15% of all state and central government jobs and places in public colleges for Dalits. All national parties are now appealing to Dalits, which is perhaps one reason why Narayanan's bid for the presidency went unopposed. The President is the fourth of seven children born to a father who practiced traditional medicine in Kerala using herbs and plants. Often his parents could not afford school fees, and Narayanan was punished for missing class until his father scraped up the rupees. He rose to become India's ambassador to the U.S. before entering politics. "A diplomat," Narayanan once said, "should have a thick skin. I got mine through experiences such as standing on a bench in front of the whole class." Narayanan sees himself as the President of all Indians, but Dalit militants fault him for not using his exalted office to help lift his fellow untouchables. However, Narayanan did not hesitate to condemn the Laxmanpur Bath atrocity as "a national shame." Dalits have yet to unite. "All that keeps India from having a bloody revolution is that we Dalits are a divided lot," says Man Dahima, a senior civil servant in Bhopal, capital of Madhya Pradesh state. Even among the Dalits, strong caste rivalries exist; one study discovered 900 Dalit "sub-castes" in the country. Basically, everyone is squirming not to fall to the bottom of India's massive pile of humanity. Predicts one Dalit official: As benefits trickle down, the conflicts between sub-castes are bound to sharpen. Lately, regional leaders have been trying to bring unity to lower-caste aspirations. So far, the only Dalit politician to challenge the mainstream parties is Kanshi Ram, 63, a former technician at a government defense laboratory. Armed with wiliness and an ability to survive in the venal world of Indian politics, Ram has no qualms about forming alliances with his high-caste adversaries if it brings his Bahujan Samaj Party to power. His abrasive protege Mayawati governed Uttar Pradesh for six months in alliance with the Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party, many of whose followers adhere stoutly to Manu's ancient law. During her term, Mayawati ordered 13,000 statues of Ambedkar to be put up and began work on a $30 million park in Lucknow in honor of the Dalit leader. She also reshuffled 1,400 bureaucrats and police officers. Dalit civil servants, whose promotions had been mothballed by their high-caste superiors, were elevated to top posts. State funds and projects for roads, schools and electricity were channeled to neglected Dalit villages. Above all, Dalits were treated to the spectacle--unimaginable a few years back--of an acid-tongued Dalit like Mayawati ordering around upper-caste grandees. Mayawati made plenty of enemies, though. She arrested thousands of political opponents, while her own Dalit-run administration was accused of corruption. Some Dalits proved as nasty as their one-time tormentors, and police were often used to settle old grievances against the upper castes. A law meant to check atrocities against Dalits was misused to send scores of innocent people to jail. Bail was denied, but bribes were gladly accepted. One former bureaucrat recounts how his own Brahman servant was accused of banditry back in his village even though the servant was then in Lucknow, hundreds of kilometers away. "It turns out the police officer in charge was a Dalit," the former bureaucrat explains. "This militancy," according to sociologist Ashis Nandy, director of the Center for the Study of Developing Societies in New Delhi, is "the price we have to pay. We are seeing an attempt by the Dalits to reaffirm their dignity. I won't say they're being provocative, but they are no longer turning the other cheek." To avoid confrontation, many Dalits are heading for the cities, which offer hope of an escape from some caste barriers. As Bindeshwar Pathak, a New Delhi social worker, says, "Can we check who cooked the meal in a hotel, or who sat beside us on a bus? Can we stop someone from living next door?" But the choice of jobs for illiterate newcomers is grim. In Bhopal, Munni Bai, mother of nine children, earns $22 a month emptying 40 latrines a day. She carries the excrement on her head, in a wicker basket she lines with newspapers. And the smell? She shrugs. "Just to fill my belly I've had to do these things," she replies. Munni Bai at least has some freedom. She probably considers herself better off than the Dalits of Khajuri, just 20 km from Bhopal, who have never heard of the great emancipator Ambedkar, who can't read or write and who are paid about $14 a month toiling for their upper-caste landlord. "There's a terror in the village. We can't speak against them or we'll be beaten," whispers one old man. Money is breaking up caste prejudices faster than any law can, and therein lies India's hope of shedding its ancient, violent yoke of discrimination. Even with such menial jobs as washing dishes or sweeping factory floors, a Dalit in the city is luckier than many of the higher-caste folks back in his country village. He may not read or write, but his children will. One Dalit returned to his Rajasthan village on a break from his city job. "The priests stop us from going into the temple. But their sons come into our house because they want to watch TV," he says. "For years they said we were dirty. But now we look much cleaner than they do." --With reporting by Faizan Ahmed /Laxmanpur Bath, Meenakshi Ganguly /Bihar, Maseeh Rahman /Lucknow and R. Bhagwan Singh /Madras

|

Jaya plays down differences with Mayawati, defends 3rd Front

Mayawati still Prime Ministerial choice: UP BSP chief

Mayawati to go Solo at all 40 Seats in Bihar

IJP to oppose projection of Mayawati as PM

Too little to show for the top slot

Mayawati never projected herself as PM candidate: TDP

INDIA ELECTION EYE-Mayawati says to go it alone in vote

Amar changes tone, says secular govt without Sonia impossible

Mayawati may align with BJP again: SP

SP will safeguard minority interests

|

rediff.com: Third Front is launched

specials.rediff.com/news/2009/mar/12sd1-third-front-launched.htm - 19k - Cached - Similar pages -

The Hindu : Front Page : Mayawati, Third Front leaders join hands

www.hindu.com/2009/03/16/stories/2009031660811200.htm - 17 hours ago - Similar pages -

'BJD open to joining UPA, Third Front'

news.rediff.com/report/2009/mar/16/inter-bjd-open-to-joining-upa-third-

The Third Front problem

www.indianexpress.com/news/the-third-front-problem/433380/ - 53k - Cached - Similar pages -

Third Front (China) - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Third_Front_(China) - 58k - Cached - Similar pages -

Third front should be revived, says Mulayam Singh

news.indiainfo.com/2005/03/25/2503mulayam.html - 38k - Cached - Similar pages -

Third front is like a 'parking lot': Venkaiah Naidu - Express India

www.expressindia.com/latest-news/Third-front-is-like-a-parking-lot-

The Hindu : Front Page : Third front to be launched today

www.thehindu.com/2009/03/12/stories/2009031258280100.htm - 24k - Cached - Similar pages -

Left Front scores, bags BJD for Third Front

ibnlive.in.com/news/left-front-scores-bags-bjd-for-third-front/87158-37.html - 43k - Cached - Similar pages -

A THIRD FRONT?

pd.cpim.org/2005/0109/01092005_edit.htm - 13k - Cached - Similar pages -

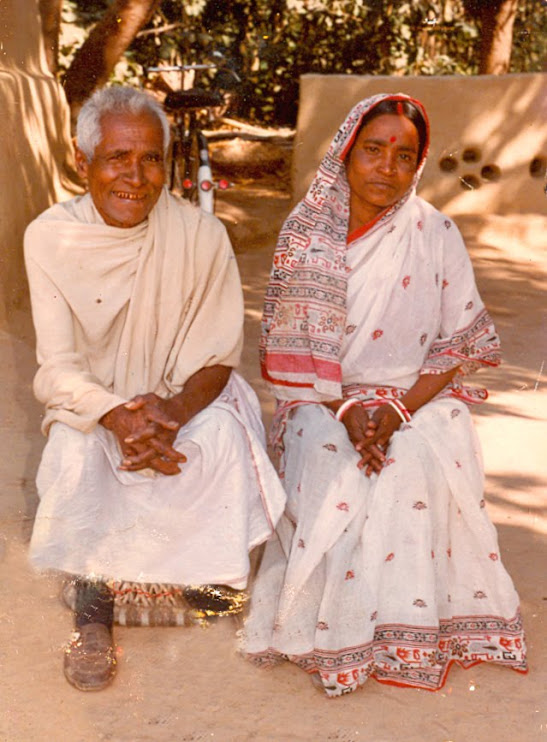

Upper caste men of Ranvir Sena

Upper caste men of Ranvir Sena  Dalits evicted by upper caste men face grim future

Dalits evicted by upper caste men face grim future

No comments:

Post a Comment